The composition root is a design pattern which helps you structure a software application by implementing a class that builds all the other classes.

In this example we will examine this pattern in Python.

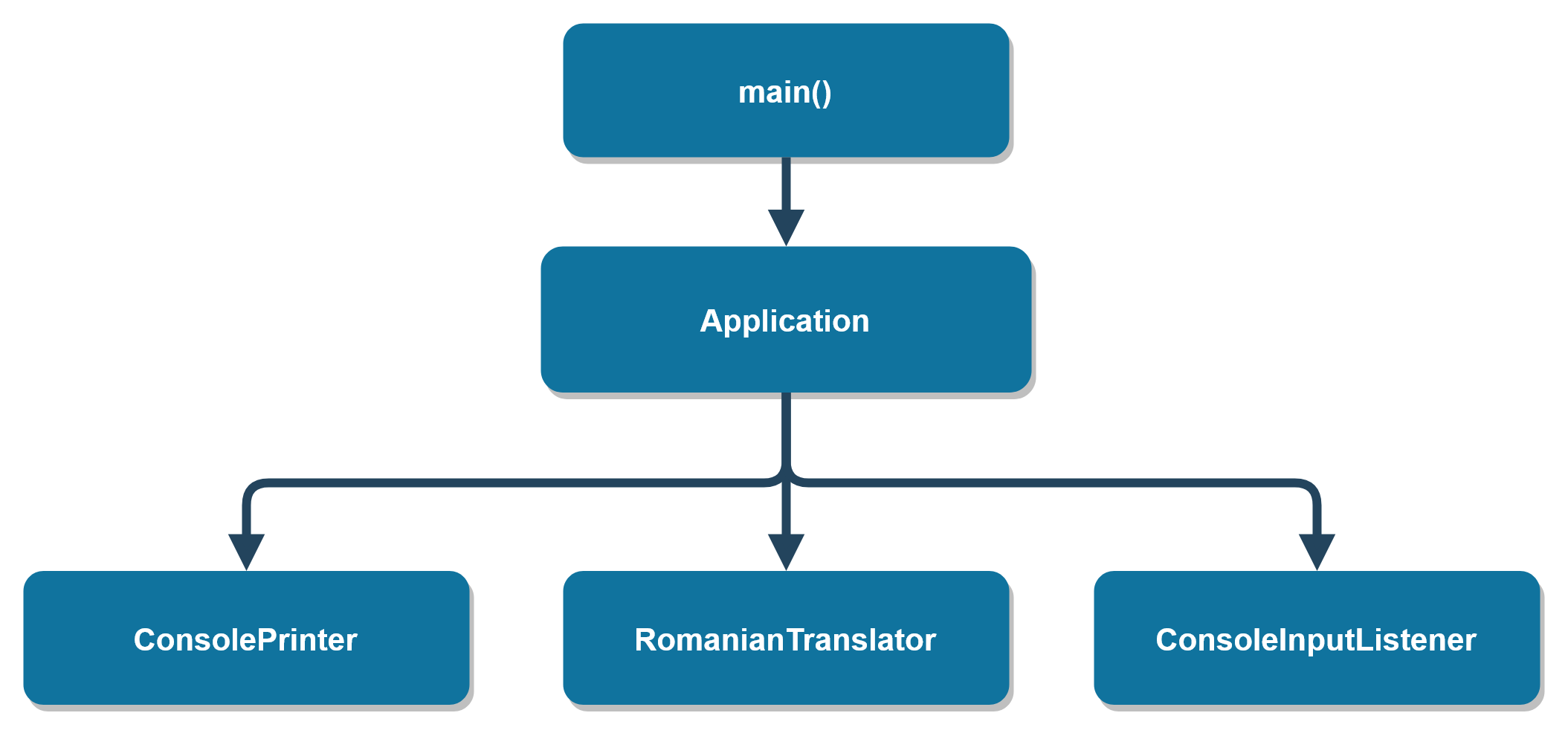

Here’s the object graph of the classes that we’re going to implement:

I have designed a sample application that we’re going to use. It contains three components: ConsoleInputListener, ConsolePrinter and RomanianTranslator and a value object class: Message.

I have designed a sample application that we’re going to use. It contains three components: ConsoleInputListener, ConsolePrinter and RomanianTranslator and a value object class: Message.

The classes are described as follows:

- Application: The composition root, glues all the classes together.

- ConsoleInputListener: Component, it reads string from the standard input.

- ConsolePrinter: Component, it prints to the standard output.

- RomanianTranslator: Component, it translates English words to Romanian.

- Message: Value object, it encapsulates the message string.

*

Program to an interface not an implementation *

Before implementing the Application component, I’m going to define the interfaces for the ConsoleInputListener, ConsolePrinter and RomanianTranslator. I’m going to call them InputListener, Printer and Translator for simplicity.

The reason I’m defining interfaces* is because I want to be able to swap the objects that the Application class references. In Python variables don’t constrain me to any type, but if I’m going to implement other objects, I’d like to have a template so it will help me reduce the number of mistakes that I can make.

Python doesn’t have support for interfaces so I’m going to use abstract classes:

| |

class Printer(metaclass=abc.ABCMeta): def print(self, message): raise NotImplementedError(“print is not implemented”)

class InputListener(metaclass=abc.ABCMeta): def get_input(self) -> str: raise NotImplementedError(“get_input is not implemented!”)

class Translator(metaclass=abc.ABCMeta): def translate(self, message: Message) -> Message: raise NotImplementedError(“translate must be implemented!”)

| |

Every class that extends my abstract classes must implement it’s abstract methods:

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

starting application. < hello Denis! > salut Denis! ``` - - - - - - Now, most real world applications aren’t this simple, the reason we went through all this code in order to implement a simple *hello world* is the following: Imagine that you have 10 translators: English, French, German… and two Printers: Console and File. You could modify the application code to take in two parameters: translator and printer use the arguments to instantiate the correct translator and printer without needing to change the other classes. You can add as many printers, translators and input listeners as you wish. That’s a huge benefit. If you were to inline all the code in a single class, adding more translations and more printing options would have been very painful and frustrating. I hope my article gave you some insight into the Composition Root pattern, if I made any mistake please feel free to correct me. 🙂 The full code is on my [Github](https://github.com/dnutiu/NucuLabs-code/tree/master/python-component-root-design-pattern). Thanks for reading!